Well Illustrated: Patients finding their voice through art

Nina Beaty is an artist and an art therapist. In 2014, a diagnosis of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) with a short life expectancy turned her life upside down. When her cancer didn't respond to standard treatment, she enrolled in an immunotherapy trial. Four years out, Nina has no evidence of cancer.

Throughout her experience with cancer, Nina turned to her love of painting and illustration to express her emotions. We sat down with Nina to learn how art helped her express herself when words failed.

Can you start by telling us a little bit about yourself?

I grew up in Manhattan in an artistic family and my interests were both in psychology and art. My BFA was in film animation and about a decade later, I got my MA and became a licensed art therapist. I seem to have gravitated towards being with others when their lives were on the line. Looking back, this inclination may have stemmed from my family history: one of my brothers died of asthma, my mother had lung cancer and my grandfather had jaw and throat cancer. Illness certainly was never foreign to me.

How were you diagnosed?

I was visiting my mom at the same time that her radiologist was. Over lunch, Dr. Henschke asked me if I ever had a scan for lung cancer. I’d quit smoking 30 years ago but she convinced me to get one anyway. That’s how I found out I had small-cell lung cancer.

I was in shock. I had always been healthy. But I owe my life to that early detection. Usually, SCLC patients die within three to six months because they’re not diagnosed in time. I was told that my SCLC was treatable but then I went online to find out that on standard chemo and radiation, I may still get only a year to live. Fortunately for me, the odds turned out better than that.

How did you decide to take part in a clinical trial? What was that experience like for you?

Once the chemo and radiation stopped working, I was offered the opportunity to screen for an immunotherapy trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering. I was accepted, and the treatment has worked and continues to work. This trial is what really keeps me going. Literally.

Immunotherapy has helped you heal physically; did art help you heal emotionally?

When I was an art therapist, I loved how the art could be used to get a peek inside someone’s mind, then explore what was expressed by the images; it worked the same way for me as a cancer patient.

There’s a numbness that comes with having cancer. Looking back, I had become a robot going through what I needed to get through to survive. I never cried the whole time. But if you look at my artwork, that’s where I showed how I was really feeling.

Art is really personal. You have to give up so much of yourself during treatment, but if you make art, you get yourself back. It’s something tangible that reminds you of who you are other than or alongside being a cancer patient. Using my art, I was able to explore my spiritual beliefs and questions I had about death and dying. I got into some existential stuff about where am I going, what am I doing? And even some more macabre thoughts — what will my urn look like? I was able to explore these ideas for myself because no one near me really wanted to talk about things like that. I was able to gather my thoughts through my art.

You created artwork for others as you were going through cancer as well. Can you talk about that?

As a patient, I connected to doctors, nurses and cancer friends through art I made for them. I’d draw cartoons, just for fun — a thank you gift to say, "I appreciate you" and to lift their spirits.

If you talk to cancer patients, many of them are aware that in some ways it’s easier to be a patient. Loved ones shut down — they don’t know what to do or say. So, art-making can be a bridge, a way to get back into a conversation when people don’t know what to say to you. It’s a way to connect and remind them that you’re still human, you’re still you — the art you share can replace an awkward moment with a spontaneous reaction/interaction.

Did that inspire the EmPatStickers? How did it become your “legacy project”?

When I was in treatment, I didn’t have the energy to stay in touch with a lot of people. I wanted to, but it was too much for me. I would look at my phone and think, “Maybe I’ll just send an emoji.” None of the standard emojis were useful. They had nothing to do with me or with the experience of living with cancer.

A bit later, when I was on the mend, I thought, “Why don’t I create a set of short animated emojis that cancer patients and their loved ones could use to text each other?” I talked to patients, social workers, doctors, nurses, and friends to figure out which images would best express the range of feelings we were going through. I subtitled it my “legacy project” because it’s the most meaningful thing I’ve ever done in my life. The EmPatStickers are my gift to the cancer world — available on iTunes and Google Play free of charge. I hope some of you will find them useful too.

Antidote featured you and EmPat stickers at the SCOPE conference earlier this year. What did it mean to you to have your stickers and your story reaching such an industry-specific audience?

I’ve been to a few events where I sit with pharma people and share my story. It’s so special to interact. It’s not often that they get to meet patients that they’ve been saving and less often that I get to thank them. I couldn’t be more grateful.

Nina’s Work: Exploring Paintings Created While in Treatment

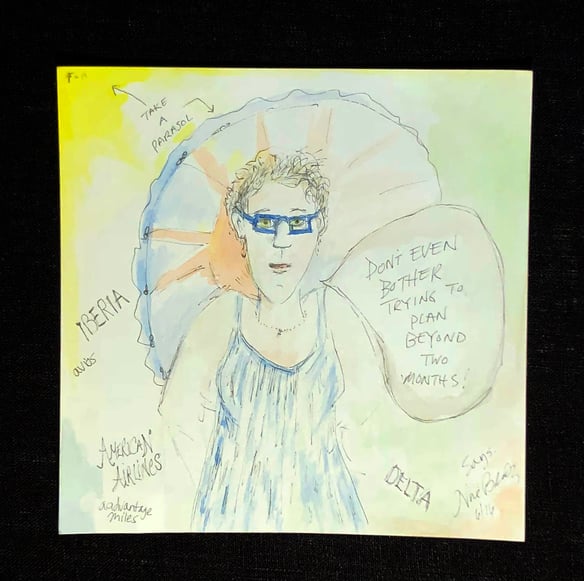

Here’s one where I was contending with my new reality. “Don’t even bother trying to plan beyond two months.” Basically, I couldn’t plan beyond two months because I didn’t know if I’d be alive — no trip planning, no thinking about the future. This was so disconcerting for me. The thing about these cancers is that they come on so quickly, at least mine did. So you really have to be flexible because your whole lifestyle has to change.

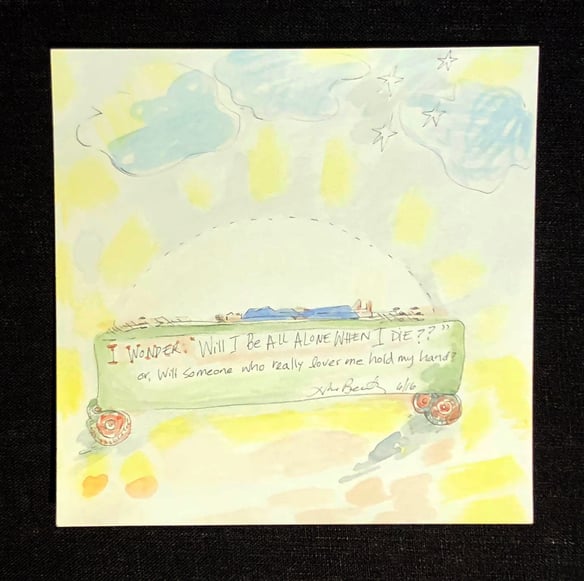

This one is me thinking about dying. “Will I be alone when I die?” It’s a real fear, and it becomes ever more real when you’re diagnosed with cancer. This was really intense, but where else can you say these thoughts?

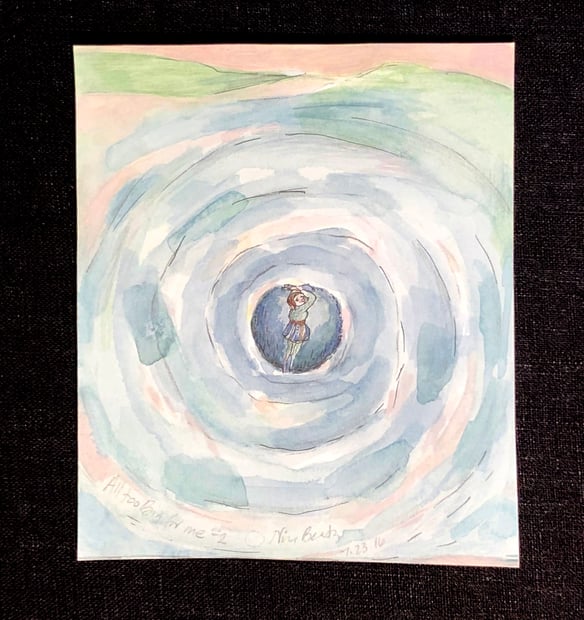

This one was a recurring image for me: trapped in the core of the earth with the whole world being too big for me. This is when I started getting better. Interestingly, the depression came when I realized I was surviving — when you’re diagnosed, your world shuts down and you are focused on doing what you need to do to live. You’ve got binoculars on and you’re looking only at your cancer and your treatment. And then suddenly you’re getting better and you can see the whole stage and everything, and it was just too much for me. This is when I started seeing a social worker — once the job of getting through treatment was over, I needed help getting back my confidence and finding a new purpose.

For more information on the importance of storytelling around clinical trials, click here. To share your story with Antidote, click here.

And, if you’re interested in looking for a trial, start searching today:

Topics: For Patients